I took the implied 10-year breakeven inflation rate from US TIPS, minus the 10-year interest rate differential, plus the real appreciation Japan would experience if the real exchange rate against the dollar 10 years from now were to return to its level in January 2010. You can adjust this as you like with whatever your estimate of the difference between the 1-2010 rate and the equilibrium rate is; it will just shift the line up or down.The result is inflation expectations just below 0 until the start of 2012. Expectations rise to almost 3% by May 2013, then fall to around 1.5% by July 2013. Krugman writes:

I have my doubts about the apparent decline in recent months. It’s being driven not by events in Japan but by the taper scare, which drove up US rates. There is a question about why that rise in US rates didn’t produce a lot more yen depreciation, but something seems off here.

The main point, however, is that this measure does suggest a substantial rise in expected inflation since Abenomics began, which is good news.Another indicator of inflation expectations is the Bank of Japan's Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior. According to this survey, there is no evidence of a decline in inflation expectations in recent months. The most recent survey, from June 2013, shows a continued rise in one-year-ahead expectations from December to March to June. The June average expectation was 5.1% and the median expectation was 3%. In 2010, the median expectation was 0% and the mean around 2%. Longer-term inflation expectations (which should correspond more closely to Krugman's measure) are also rising, though more gradually.

|

| Source: Bank of Japan Opinion Survey |

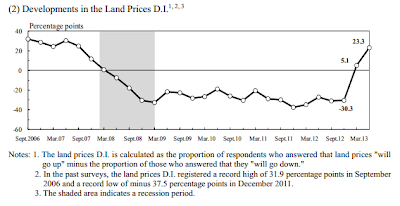

Also at a new high is the survey's measure of land price expectations. This is a newer development; the sharp rise began in late 2012:

Even if the expectations reported by surveyed households are not an accurate indicator of what will actually happen with inflation, they are still relevant. In the United States, households in the Michigan Survey of Consumers report higher inflation expectations than professional forecasts or TIPS-based measures. A new paper by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Olivier Coibion, summarized by Jim Hamilton, suggests that the household expectations are important in explaining the "missing deflation" of the past few years.

Neither Krugman's US TIPS-based measure nor the household survey-based measure are perfect indicators of Japanese inflation expectations. But the fact that both indicate a rise in expectations since Abenomics began, combined with the dramatic increase in the index of land price expectations, convinces me at least qualitatively that expectations are rising, though I'd put huge error bars on any quantitative estimate.

Krugman calls the rise in inflation expectations "good news." I agree, with a qualification. In an earlier post, "What Does Abenomics Feel Like?", I noted that Japanese consumers viewed rising prices extremely unfavorably. This, unsurprisingly, has not changed. There are, after all, no significant changes in perceptions of employment and working conditions. In the mind of a typical consumer, more concerned with her own purchasing power than with liquidity trap economics, rising prices are not such a signifier of salvation.

But there is a glimmer of hope. Consumers' perceptions of current economic conditions and of the economy's growth potential are both looking-- well, not bright, but brighter than before.