In recent months, there has been no notable change in inflation uncertainty at either horizon.

Showing posts with label consumers. Show all posts

Showing posts with label consumers. Show all posts

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Consumer Inflation Uncertainty Holding Steady

I recently updated my Consumer Inflation Uncertainty Index through October 2017. Data is available here and the official (gated) publication in the Journal of Monetary Economics is here. Inflation uncertainty remains low by historic standards. Uncertainty about longer-run (5- to 10-year ahead) inflation remains lower than uncertainty about next-year inflation.

The average "less uncertain" type consumer still expects longer-run inflation around 2.4%, while the longer-run inflation forecasts of "highly uncertain" consumers have risen in recent months to the 8-10% range.

Thursday, September 28, 2017

An Inflation Expectations Experiment

Last semester, my senior thesis advisee Alex Rodrigue conducted a survey-based information experiment via Amazon Mechanical Turk. We have coauthored a working paper detailing the experiment and results titled "Household Informedness and Long-Run Inflation Expectations: Experimental Evidence." I presented our research at my department seminar yesterday with the twin babies in tow, and my tweet about the experience is by far my most popular to date:

As shown in the figure above, before receiving the treatments, very few respondents forecast 2% inflation over the long-run and only about a third even forecast in the 1-3% range. Over half report a multiple-of-5% forecast, which, as I argue in a recent paper in the Journal of Monetary Economics, is a likely sign of high uncertainty. When presented with a graph of the past 15 years of inflation, or with the FOMC statement announcing the 2% target, the average respondent revises their forecast around 2 percentage points closer to the target. Uncertainty also declines.

The results are consistent with imperfect information models because the information treatments are publicly available, yet respondents still revise their expectations after the treatments. Low informedness is part of the reason why expectations are far from the target. The results are also consistent with Bayesian updating, in the sense that high prior uncertainty is associated with larger revisions. But equally noteworthy is the fact that even after receiving both treatments, expectations are still quite heterogeneous and many still substantially depart from the target. So people seem to interpret the information in different ways and view it as imperfectly credible.

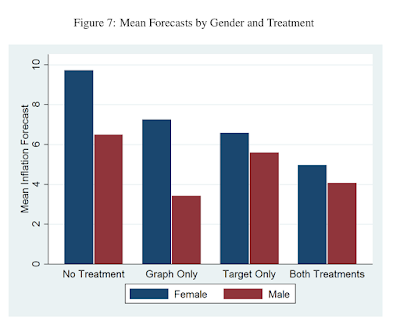

We look at how treatment effects vary by respondent characteristic. One interesting result is that, after receiving both treatments, the discrepancy between mean male and female inflation expectations (which has been noted in many studies) nearly disappears (see figure below).

There is more in the paper about how treatment effects vary with other characteristics, including respondents' opinion of government policy and their prior knowledge. We also look at whether expectations can be "un-anchored from below" with the graph treatment.

Consumers' inflation expectations are very disperse; on household surveys, many people report long-run inflation expectations that are far from the Fed's 2% target. Are these people unaware of the target, or do they know it but remain unconvinced of its credibility? In another paper in the Journal of Macroeconomics, I provide some non-experimental evidence that public knowledge of the Fed and its objectives is quite limited. In this paper, we directly treat respondents with information about the target and about past inflation, in randomized order, and see how they revise their reported long-run inflation expectations. We also collect some information about their prior knowledge of the Fed and the target, their self-reported understanding of inflation, and their numeracy and demographic characteristics. About a quarter of respondents knew the Fed's target and two-thirds could identify Yellen as Fed Chair from a list of three options.I gave a 90 minute econ seminar today with the twin babies, both awake. Held one and audience passed the other around. A first in economics?— Carola Conces Binder (@cconces) September 28, 2017

As shown in the figure above, before receiving the treatments, very few respondents forecast 2% inflation over the long-run and only about a third even forecast in the 1-3% range. Over half report a multiple-of-5% forecast, which, as I argue in a recent paper in the Journal of Monetary Economics, is a likely sign of high uncertainty. When presented with a graph of the past 15 years of inflation, or with the FOMC statement announcing the 2% target, the average respondent revises their forecast around 2 percentage points closer to the target. Uncertainty also declines.

The results are consistent with imperfect information models because the information treatments are publicly available, yet respondents still revise their expectations after the treatments. Low informedness is part of the reason why expectations are far from the target. The results are also consistent with Bayesian updating, in the sense that high prior uncertainty is associated with larger revisions. But equally noteworthy is the fact that even after receiving both treatments, expectations are still quite heterogeneous and many still substantially depart from the target. So people seem to interpret the information in different ways and view it as imperfectly credible.

We look at how treatment effects vary by respondent characteristic. One interesting result is that, after receiving both treatments, the discrepancy between mean male and female inflation expectations (which has been noted in many studies) nearly disappears (see figure below).

There is more in the paper about how treatment effects vary with other characteristics, including respondents' opinion of government policy and their prior knowledge. We also look at whether expectations can be "un-anchored from below" with the graph treatment.

Thursday, September 14, 2017

Consumer Forecast Revisions: Is Information Really so Sticky?

My paper "Consumer Forecast Revisions: Is Information Really so Sticky?" was just accepted for publication in Economics Letters. This is a short paper that I believe makes an important point.

Then I transform the data so that it is like the MSC data. First I round the responses to the nearest integer. This makes the updating frequency estimates decrease a little. Then I look at it at the six-month frequency instead of monthly. This makes the updating frequency estimates decrease a lot, and I find similar estimates to the previous literature-- updates about every 8 months.

So low-frequency data, and, to a lesser extent, rounded responses, result in large underestimates of revision frequency (or equivalently, overestimates of information stickiness). And if information is not really so sticky, then sticky information models may not be as good at explaining aggregate dynamics. Other classes of imperfect information models, or sticky information models combined with other classes of models, might be better.

Read the ungated version here. I will post a link to the official version when it is published.

Sticky information models are one way of modeling imperfect information. In these models, only a fraction (λ) of agents update their information sets each period. If λ is low, information is quite sticky, and that can have important implications for macroeconomic dynamics. There have been several empirical approaches to estimating λ. With micro-level survey data, a non-parametric and time-varying estimate of λ can be obtained by calculating the

fraction of respondents who revise their forecasts (say, for inflation) at each survey date. Estimates from the Michigan Survey of Consumers (MSC) imply that consumers update their information about inflation approximately once every 8 months.

Here are two issues that I point out with these estimates:

I show that several issues with estimates of information stickiness based on consumer survey microdata lead to substantial underestimation of the frequency with which consumers update their expectations. The first issue stems from data frequency. The rotating panel of Michigan Survey of Consumer (MSC) respondents take the survey twice with a six-month gap. A consumer may have the same forecast at months t and t+ 6 but different forecasts in between. The second issue is that responses are reported to the nearest integer. A consumer may update her information, but if the update results in a sufficiently small revisions, it will appear that she has not updated her information.To quantify how these issues matter, I use data from the New York Fed Survey of Consumer Expectations, which is available monthly and not rounded to the nearest integer. I compute updating frequency with this data. It is very high-- at least 5 revisions in 8 months, as opposed to the 1 revision per 8 months found in previous literature.

Then I transform the data so that it is like the MSC data. First I round the responses to the nearest integer. This makes the updating frequency estimates decrease a little. Then I look at it at the six-month frequency instead of monthly. This makes the updating frequency estimates decrease a lot, and I find similar estimates to the previous literature-- updates about every 8 months.

So low-frequency data, and, to a lesser extent, rounded responses, result in large underestimates of revision frequency (or equivalently, overestimates of information stickiness). And if information is not really so sticky, then sticky information models may not be as good at explaining aggregate dynamics. Other classes of imperfect information models, or sticky information models combined with other classes of models, might be better.

Read the ungated version here. I will post a link to the official version when it is published.

Monday, April 17, 2017

EconTalk on the Economics of Pope Francis

Russ Roberts recently interviewed Robert Whaples on the EconTalk podcast, which I have listened to regularly for years. I was especially interested when I saw the title of this episode, The Economics of Pope Francis, both because I am a Catholic and because I generally find Roberts' discussions of religion (from his Jewish perspective) interesting and so articulate that they help me clarify my own thinking, even if my views diverge from his.

In this episode, Roberts and Whaples, an economics professor at Wake Forest and convert to Catholicism, discuss the Pope's 2015 encyclical Laudato Si, which focuses on environmental issues and issues of markets, capitalism, and inequality more broadly. Given Roberts' strong support of free markets in most circumstances, I was pleased and impressed that he did not simply dismiss the Pope's work as anti-market, as many have. Near the end of the episode, Roberts says:

when I think about people who are hostile to capitalism, per se, I would argue that capitalism is not the problem. It's us. Capitalism is, what it's really good at, is giving us what we want--more or less...And so, if you want to change capitalism, you've got to change us. And that's--I really see that--I like the Pope doing that. I'm all for that.

I agree with Roberts' point that one place where religious leaders have an important role to play in the economy is in guiding the religious toward changing, or at least managing, their desires. Whaples discusses this too, summarizing the encyclical as being mainly about people's excessive focus on consumption:

It's mainly on the--the point we were talking about before, consuming too much. It's exhortation. He is basically saying what has been said by the Church for the last 2000 year...Look, you don't need all this stuff. It's pulling you away from the ultimate ends of your life. You are just pursuing it and not what you are meant, what you were created by God to pursue. You were created by God to pursue God, not to pursue this Mammon stuff.

Roberts and Whaples both agree that a lot of problems that are typically blamed on market capitalism could be improved if people's desires changed, and that religion can play a role in this (though they acknowledge that some non-religious people also turn away from materialism for various reasons.) Roberts' main criticism of the encyclical, however, is that: "The problem is the document has got too much other stuff there...it comes across as an institutional indictment, and much less an indictment of human frailty."

I would add, though, that just as markets reflect human wants, so do institutions, whether deliberately designed or developed and evolved more organically. So it is not totally clear to me that we can separate "indictment of human frailty" and "institutional indictment." No economic institutions are totally value-neutral, even free markets. Institutions and preferences co-evolve, and institutions can even shape preferences. And the Pope is of course the head of one of the oldest and largest institutions in the world, so it does not seem beyond his role to comment on institutions as an integral part of his exhortation to his flock.

Friday, April 7, 2017

Happiness as a Macroeconomic Policy Objective

Economists have mixed opinions about the degree to which subjective wellbeing and happiness should guide policymaking. Wouter den Haan, Martin Ellison, Ethan Ilzetzki, Michael McMahon, and Ricardo Reis summarize a recent survey of European economists by the Centre for Macroeconomics and CEPR. They note that the survey "finds a reasonable amount of openness to wellbeing measures among European macroeconomists. On balance, though, there remains a strong sense that while these measures merit further research, we are a long way off reaching a point where they are widely accepted and sufficiently reliable for macroeconomic analysis and policymaking."

As the authors note, the idea that happiness should be a primary focus of economic policy is central to Jeremy Bentham's "maximum happiness principle." Bentham is considered the founder of utilitarianism. Though the incorporation of survey-based quantitative measures of subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction is a relatively recent development in economics, utilitarianism, of course, is not. Notably, John Stuart Mill and many classical economists including William Stanley Jevons, Alfred Marshall, and Francis Edgeworth were deeply influenced by Bentham.

These classical economists might have been perplexed to see the results of Question 2 of the recent survey of economists, which asked whether quantitative wellbeing analysis should play an important role in guiding policymakers in determining macroeconomic policies. The responses, shown below, reveal slightly more negative than positive responses to the question. And yet, what macroeconomists and macroeconomic policymakers do today descends directly from the strategies for "quantitative wellbeing analysis" developed by classical economists.

In The Theory of Political Economy (1871), for example, Jevons wrote:

The focus on happiness survey data I think stems from recognition of some of the problems with the assumptions that allow us to link GDP to consumption to utility, for example, stable and exogenous preferences and interpersonally comparable utility functions (that depend exclusively on one's own consumption). One approach is to relax these assumptions (and introduce others) by, for example, using more complicated utility functions with additional arguments and/or changing preferences. So we see models with habit formation and "keeping up with the Joneses" effects.

Another approach is to ask people directly about their happiness. This, of course, introduces its own issues of methodology and interpretation, as many of the economist panelists point out. Michael Wickens, for example, notes that the “original happiness literature was in reality a measure of unhappiness: envy over income differentials, illness, divorce, being unmarried etc” and that “none of these is a natural macro policy objective.”

I think that responses to subjective happiness questions also include some backward-looking and some forward-looking components; happiness depends on what has happened to you and what you expect to happen in the future. This makes it hard for me to imagine how to design macroeconomic policy to formally target these indicators, and makes me tend to agree with Reis' opinion that they should be used as “complements to GDP though, not substitutes.”

As the authors note, the idea that happiness should be a primary focus of economic policy is central to Jeremy Bentham's "maximum happiness principle." Bentham is considered the founder of utilitarianism. Though the incorporation of survey-based quantitative measures of subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction is a relatively recent development in economics, utilitarianism, of course, is not. Notably, John Stuart Mill and many classical economists including William Stanley Jevons, Alfred Marshall, and Francis Edgeworth were deeply influenced by Bentham.

These classical economists might have been perplexed to see the results of Question 2 of the recent survey of economists, which asked whether quantitative wellbeing analysis should play an important role in guiding policymakers in determining macroeconomic policies. The responses, shown below, reveal slightly more negative than positive responses to the question. And yet, what macroeconomists and macroeconomic policymakers do today descends directly from the strategies for "quantitative wellbeing analysis" developed by classical economists.

|

| Source: http://voxeu.org/article/views-happiness-and-wellbeing-objectives-macroeconomic-policy |

"A unit of pleasure or pain is difficult even to conceive; but it is the amount of these feelings which is continually prompting us to buying and selling, borrowing and lending, labouring and resting, producing and consuming; and it is from the quantitative effects of the feelings that we must estimate their comparative amounts."Hence generations of economists have been trained in welfare economics based on utility theory, in which utility is an increasing function of consumption, u(c). Under neoclassical assumptions-- cardinal utility, stable preferences, diminishing marginal utility, and interpersonally comparable utility functions-- trying to maximize a social welfare function that is just the sum of all individual utility functions is totally Benthamite. And a focus on GDP growth is very natural, as more income should mean more consumption.

The focus on happiness survey data I think stems from recognition of some of the problems with the assumptions that allow us to link GDP to consumption to utility, for example, stable and exogenous preferences and interpersonally comparable utility functions (that depend exclusively on one's own consumption). One approach is to relax these assumptions (and introduce others) by, for example, using more complicated utility functions with additional arguments and/or changing preferences. So we see models with habit formation and "keeping up with the Joneses" effects.

Another approach is to ask people directly about their happiness. This, of course, introduces its own issues of methodology and interpretation, as many of the economist panelists point out. Michael Wickens, for example, notes that the “original happiness literature was in reality a measure of unhappiness: envy over income differentials, illness, divorce, being unmarried etc” and that “none of these is a natural macro policy objective.”

I think that responses to subjective happiness questions also include some backward-looking and some forward-looking components; happiness depends on what has happened to you and what you expect to happen in the future. This makes it hard for me to imagine how to design macroeconomic policy to formally target these indicators, and makes me tend to agree with Reis' opinion that they should be used as “complements to GDP though, not substitutes.”

Sunday, January 8, 2017

Post-Election Political Divergence in Economic Expectations

"Note that among Democrats, year-ahead income expectations fell and year-ahead inflation expectations rose, and among Republicans, income expectations rose and inflation expectations fell. Perhaps the most drastic shifts were in unemployment expectations:rising unemployment was anticipated by 46% of Democrats in December, up from just 17% in June, but for Republicans, rising unemployment was anticipated by just 3% in December, down from 41% in June. The initial response of both Republicans and Democrats to Trump’s election is as clear as it is unsustainable: one side anticipates an economic downturn, and the other expects very robust economic growth."This is from Richard Curtin, Director of the Michigan Survey of Consumers. He is comparing the economic sentiments and expectations of Democrats, Independents, and Republicans who took the survey in June and December 2016. A subset of survey respondents take the survey twice, with a six-month gap. So these are the respondents who took the survey before and after the election. The results are summarized in the table below, and really are striking, especially with regards to unemployment. Inflation expectations also rose for Democrats and fell for Republicans (and the way I interpret the survey data is that most consumers see inflation as a bad thing, so lower inflation expectations means greater optimism.)

Notice, too, that self-declared Independents are more optimistic after the election than before. More of them are expecting lower unemployment and fewer are expecting higher unemployment. Inflation expectations also fell from 3% to 2.3%, and income expectations rose. Of course, this is likely based on a very small sample size.

|

| Source: Richard Curtin, Michigan Survey of Consumers |

Saturday, December 31, 2016

Pushing the Boundaries of Economics

As a macroeconomist, I mostly research the types of concepts that are more traditionally associated with economics, like inflation and interest rates. But one of the great things about economics training, in my opinion, is that you receive enough general training to be able to follow much of what is going on in other fields. It is always interesting for me to read papers or attend seminars in applied microeconomics to see the wide (and expanding) scope of the discipline.

Gary Becker won the Nobel Prize in 1992 "for having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behaviour and interaction, including nonmarket behaviour" and "to aspects of human behavior which had previously been dealt with by other social science disciplines such as sociology, demography and criminology." The Freakonomics books and podcast have gone a long way in popularizing this approach. But it is not without its critics, both within and outside the profession.

For all that the economic way of thinking and the quantitative tools of econometrics can add in addressing a boundless variety of questions, there is also much that our analysis and tools leave out. In areas like health or criminology, the assumptions and calculations that seem perfectly reasonable to an economist may seem anywhere from misguided to offensive to a medical doctor or criminologist. Roland Fryer's working paper on racial differences in police use of force, for example, was prominently covered with both praise and criticism.

Another NBER working paper, released this week by Jonathan de Quidt and Johannes Haushofer, is also pushing the boundaries of economics, arguing that "depression has not received significant attention in the economics literature." By depression, they are referring to major depressive disorder (MDD), not a particularly severe recession. While neither of the authors holds a medical degree, Haushofer holds doctorates in both economics and neurobiology. In "Depression for Economists," they build a model in which individuals choose to exert either high or low effort; depression is induced by a negative "shock" to an individual's belief about her return to high effort.

In the model, the individual's income depends on her effort, amount of sleep, and food consumption. Her utility depends on her sleep, food consumption, and non-food consumption. She maximizes utility given her belief about her return to effort, which she updates in a Bayesian manner. If her belief about her return to effort declines (synonymous in the model to becoming depressed), she exerts less labor effort. Her total (food and non-food) consumption and utility unambiguously decrease, leading to "depressed mood." In the extreme, she may reduce her labor effort to zero, at which point she would stop learning more about her return to effort and get stuck in a "poverty trap."

The depressed individual's sleeping and food consumption may either increase or decrease, as consumption motives become more important relative to production motives. In other words, she sleeps and eats closer to the amounts that she would choose if she cared only about the utility directly from sleeping and eating, and not about how her sleeping and eating choices affect her ability to produce.

While this result does match the empirical findings in the medical literature that depression may either reduce or increase sleep duration and lead to either over- or under-eating, it seems implausible to me that depressed individuals sleep ten or more hours a day because they just love sleeping, or lose their appetite because they don't enjoy food beyond its ability to help them be productive. I'm not an expert, but from what I understand there are physiological and chemical reasons for the change in sleep patterns and appetite that could be independent of a person's beliefs about their returns to labor effort.

However, the authors argue that an "advantage of our model is that it resonates with prominent psychological and psychiatric theories of depression, and the therapeutic approaches to which they gave rise." They refer in particular to "Charles Ferster, who argued that depression resulted from an overexposure to negative reinforcement and underexposure to positive reinforcement in the environment (Ferster 1973)...Ferster’s account of the etiology of depression is in line with how we model depression here, namely as a consequence of exposure to negative shocks." They also refer to the work of psychiatrist Aaron Beck (1967), whose suggested that depression arises from "distorted thinking" motivates the use of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a standard treatment for depression.

The authors note that "Our main goal in writing this paper was to give economists a starting point for thinking and writing about depression using the language of economics. We have therefore kept the model as simple as possible." They also steer clear of suggesting any policy implications (other than implicitly providing support for CBT.) It will be fascinating to see whether and how the medical community responds, and also to hear from economists who have themselves experienced depression.

Gary Becker won the Nobel Prize in 1992 "for having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behaviour and interaction, including nonmarket behaviour" and "to aspects of human behavior which had previously been dealt with by other social science disciplines such as sociology, demography and criminology." The Freakonomics books and podcast have gone a long way in popularizing this approach. But it is not without its critics, both within and outside the profession.

For all that the economic way of thinking and the quantitative tools of econometrics can add in addressing a boundless variety of questions, there is also much that our analysis and tools leave out. In areas like health or criminology, the assumptions and calculations that seem perfectly reasonable to an economist may seem anywhere from misguided to offensive to a medical doctor or criminologist. Roland Fryer's working paper on racial differences in police use of force, for example, was prominently covered with both praise and criticism.

Another NBER working paper, released this week by Jonathan de Quidt and Johannes Haushofer, is also pushing the boundaries of economics, arguing that "depression has not received significant attention in the economics literature." By depression, they are referring to major depressive disorder (MDD), not a particularly severe recession. While neither of the authors holds a medical degree, Haushofer holds doctorates in both economics and neurobiology. In "Depression for Economists," they build a model in which individuals choose to exert either high or low effort; depression is induced by a negative "shock" to an individual's belief about her return to high effort.

In the model, the individual's income depends on her effort, amount of sleep, and food consumption. Her utility depends on her sleep, food consumption, and non-food consumption. She maximizes utility given her belief about her return to effort, which she updates in a Bayesian manner. If her belief about her return to effort declines (synonymous in the model to becoming depressed), she exerts less labor effort. Her total (food and non-food) consumption and utility unambiguously decrease, leading to "depressed mood." In the extreme, she may reduce her labor effort to zero, at which point she would stop learning more about her return to effort and get stuck in a "poverty trap."

The depressed individual's sleeping and food consumption may either increase or decrease, as consumption motives become more important relative to production motives. In other words, she sleeps and eats closer to the amounts that she would choose if she cared only about the utility directly from sleeping and eating, and not about how her sleeping and eating choices affect her ability to produce.

While this result does match the empirical findings in the medical literature that depression may either reduce or increase sleep duration and lead to either over- or under-eating, it seems implausible to me that depressed individuals sleep ten or more hours a day because they just love sleeping, or lose their appetite because they don't enjoy food beyond its ability to help them be productive. I'm not an expert, but from what I understand there are physiological and chemical reasons for the change in sleep patterns and appetite that could be independent of a person's beliefs about their returns to labor effort.

However, the authors argue that an "advantage of our model is that it resonates with prominent psychological and psychiatric theories of depression, and the therapeutic approaches to which they gave rise." They refer in particular to "Charles Ferster, who argued that depression resulted from an overexposure to negative reinforcement and underexposure to positive reinforcement in the environment (Ferster 1973)...Ferster’s account of the etiology of depression is in line with how we model depression here, namely as a consequence of exposure to negative shocks." They also refer to the work of psychiatrist Aaron Beck (1967), whose suggested that depression arises from "distorted thinking" motivates the use of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a standard treatment for depression.

The authors note that "Our main goal in writing this paper was to give economists a starting point for thinking and writing about depression using the language of economics. We have therefore kept the model as simple as possible." They also steer clear of suggesting any policy implications (other than implicitly providing support for CBT.) It will be fascinating to see whether and how the medical community responds, and also to hear from economists who have themselves experienced depression.

Monday, December 5, 2016

The Future is Uncertain, but So Is the Past

In a recently-released research note, Federal Reserve Board economists Alan Detmeister, David Lebow, and Ekaterina Peneva summarize new survey results on consumers' inflation perceptions. The well-known Michigan Survey of Consumers asks consumers about their expectations of future inflation (over the next year and 5- to 10- years), but does not ask them what they believe inflation has been in recent years.

In many macroeconomic models, inflation perceptions should be nearly perfect. After all, inflation statistics are publicly available, and anyone should be able to access them. The Federal Reserve commissioned the Michigan Survey of Consumers Research Center to survey consumers about their perceptions of inflation over the past year and over the past 5- to 10-years, using analogous wording to the questions about inflation expectations. As you might guess, consumers lack perfect knowledge of inflation in the recent past. If you're like most people (which, by dent of reading an economic blog, you are probably not), you probably haven't looked up inflation statistics or read the financial news recently.

But more surprisingly, consumers seem just as uncertain about past inflation, or even more so, as about future inflation. Take a look at these histograms of inflation perceptions and expectations from the February 2016 survey data:

Compare Panel A to Panel C. Panel A shows consumers' perceptions of inflation over the past 5- to 10-years, and Panel C shows their expectations for the next 5- to 10-years. Both panels show a great deal of dispersion, or variation across consumers. But also notice the response heaping at multiples of 5%. In both panels, over 10% of respondents choose 5%, and you also see more 10% responses than either 9% or 11% responses. In a working paper, I show that this response heaping is indicative of high uncertainty. Consumers choose a 5%, 10%, 15%, etc. response to indicate high imprecision in their estimates of future inflation. So it is quite surprising that even more consumers choose the 10, 15, 20, and 25% responses for perceptions of past inflation than for expectations of future inflation.

The response heaping at multiples of 5% is also quite substantial for short-term inflation perceptions (Panel B). Without access to the underlying data, I can't tell for sure whether it is more or less prevalent than for expectations of future short-term inflation, but it is certainly noticeable.

What does this tell us? People are just as unsure about inflation in the relatively recent past as they are about inflation in the near to medium-run future. And this says something important for monetary policymakers. A goal of the Federal Reserve is to anchor medium- to long-run inflation expectations at the 2% target. With strongly-anchored expectations, we should see most expectations near 2% with low uncertainty. If people are uncertain about longer-run inflation, it could either be that they are unaware of the Fed's inflation target, or aware but unconvinced that the Fed will actually achieve its target. It is difficult to say which is the case. The former would imply that we need more public informedness about economic concepts and the Fed, while the latter would imply that the Fed needs to improve its credibility among an already-informed public. Since perceptions are about as uncertain as expectations, this lends support to the idea that people are simply uninformed about inflation-- or that memory of economic statistics is relatively poor.

In many macroeconomic models, inflation perceptions should be nearly perfect. After all, inflation statistics are publicly available, and anyone should be able to access them. The Federal Reserve commissioned the Michigan Survey of Consumers Research Center to survey consumers about their perceptions of inflation over the past year and over the past 5- to 10-years, using analogous wording to the questions about inflation expectations. As you might guess, consumers lack perfect knowledge of inflation in the recent past. If you're like most people (which, by dent of reading an economic blog, you are probably not), you probably haven't looked up inflation statistics or read the financial news recently.

But more surprisingly, consumers seem just as uncertain about past inflation, or even more so, as about future inflation. Take a look at these histograms of inflation perceptions and expectations from the February 2016 survey data:

|

| Source: December 5 FEDS Note |

Compare Panel A to Panel C. Panel A shows consumers' perceptions of inflation over the past 5- to 10-years, and Panel C shows their expectations for the next 5- to 10-years. Both panels show a great deal of dispersion, or variation across consumers. But also notice the response heaping at multiples of 5%. In both panels, over 10% of respondents choose 5%, and you also see more 10% responses than either 9% or 11% responses. In a working paper, I show that this response heaping is indicative of high uncertainty. Consumers choose a 5%, 10%, 15%, etc. response to indicate high imprecision in their estimates of future inflation. So it is quite surprising that even more consumers choose the 10, 15, 20, and 25% responses for perceptions of past inflation than for expectations of future inflation.

The response heaping at multiples of 5% is also quite substantial for short-term inflation perceptions (Panel B). Without access to the underlying data, I can't tell for sure whether it is more or less prevalent than for expectations of future short-term inflation, but it is certainly noticeable.

What does this tell us? People are just as unsure about inflation in the relatively recent past as they are about inflation in the near to medium-run future. And this says something important for monetary policymakers. A goal of the Federal Reserve is to anchor medium- to long-run inflation expectations at the 2% target. With strongly-anchored expectations, we should see most expectations near 2% with low uncertainty. If people are uncertain about longer-run inflation, it could either be that they are unaware of the Fed's inflation target, or aware but unconvinced that the Fed will actually achieve its target. It is difficult to say which is the case. The former would imply that we need more public informedness about economic concepts and the Fed, while the latter would imply that the Fed needs to improve its credibility among an already-informed public. Since perceptions are about as uncertain as expectations, this lends support to the idea that people are simply uninformed about inflation-- or that memory of economic statistics is relatively poor.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

Independence at the CFPB and the Fed

One of my major motivations in starting this blog a few years ago was to have a space to grapple with the topic of central bank independence and accountability. One of the most important things I have learned since then is that independence and accountability are highly multi-dimensional concepts; different institutions can be granted different types of independence, and can fail to be accountable in countless ways. As a corollary, nominal or de jure independence does not guarantee de facto independence. Likewise, an institution may be accountable in name only.

A recent ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia about the independence of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) highlights the complexity of these issues. The CFPB was created under the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. On Tuesday, a three-judge panel declared that this agency's particular form of independence is unconstitutional. Most notably, the Director of the CFPB-- currently Richard Cordray-- is removable only by the President, and only for cause.

The petitioner in the case against the CFPB, the mortgage lender PHH Corporation, which was subject to a large fine from the CFPB, argued that the CFPB's structure violates Article II of the Constitution. The Appeals Court's decision provides some historical context:

Although the Federal Reserve, unlike the CFPB, has a seven-member Board of Governors, several aspects of their governance are similar: the CFPB Director, like the seven members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, is nominated by the President and approved by the Senate. The CFPB Director's term length is 5 years, compared to 14 years for the Governors-- but importantly, both have terms longer than the 4-year Presidential term. The Chair and Vice Chair of the Fed are nominated from the Governors by the President and approved by the Senate for a 4-year term. Both the CFPB Director and the Fed Chair are required to give semi-annual reports to Congress. See these resources for a more detailed comparison of the structure and governance of independent federal agencies.

I find it striking that the phrase individual liberty appears 32 times in the 110-page decision. The very first paragraph states, "This is a case about executive power and individual liberty. The U.S. Government’s executive power to enforce federal law against private citizens – for example, to bring criminal prosecutions and civil enforcement actions – is essential to societal order and progress, but simultaneously a grave threat to individual liberty."

Even though both the CFPB and the Fed have substantial financial regulatory authority, the discourse on Federal Reserve independence does not focus so heavily on liberty (I've barely come across the word at all in my readings on the subject); instead, it focuses on independence as a potential threat to accountability. As I have previously written, "the term accountability has become 'an ever-expanding concept,'" and one that is often not usefully defined. The same might be said for the term liberty. Still, the two terms have different connotations. Accountability requires that the institution carry out its responsibilities satisfactorily, while liberty is more about what the institution doesn't do.

Accountability is a key concept in the literature on delegation of tasks to technocrats or politicians. In "Bureaucrats or Politicians?," Alberto Alesini and Guido Tabellini (2007) build a model in which politicians are held accountable by their desire for re-election, while top-level bureaucrats are held accountable by "career concerns." The social desirability of delegating a task to an unelected bureaucrat depends on how the task affects the distribution of resources or advantages-- and thus, on the strength of interest-group political pressure. As Alan Blinder writes:

Tyler Cowen writes, "I say the regulatory state already has too much arbitrary power, and this [District Court ruling] is a (small) move in the right direction." It is not the reduction of the regulatory state's power that will necessarily enhance either accountability or liberty, but the reduction of the arbitrariness of the regulatory power. This can come about through transparency (which the Fed typically cites as key to the maintenance of accountability), making policies and enforcement more predictable and less retroactive and reducing uncertainty. I don't know that the types of governance changes implied by the District Court ruling (if it holds) will substantially affect the CFPB's transparency or make it any less capable of pursuing its goals, as I tend to agree with Senator Elizabeth Warren's interpretation that the ruling will only require “a small technical tweak.”

A recent ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia about the independence of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) highlights the complexity of these issues. The CFPB was created under the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. On Tuesday, a three-judge panel declared that this agency's particular form of independence is unconstitutional. Most notably, the Director of the CFPB-- currently Richard Cordray-- is removable only by the President, and only for cause.

The petitioner in the case against the CFPB, the mortgage lender PHH Corporation, which was subject to a large fine from the CFPB, argued that the CFPB's structure violates Article II of the Constitution. The Appeals Court's decision provides some historical context:

"To carry out the executive power and be accountable for the exercise of that power, the President must be able to control subordinate officers in executive agencies. In its landmark decision in Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52 (1926), authored by Chief Justice and former President Taft, the Supreme Court therefore recognized the President’s Article II authority to supervise, direct, and remove at will subordinate officers in the Executive Branch.The decision goes on to add that "No head of either an executive agency or an independent agency operates unilaterally without any check on his or her authority. Therefore, no independent agency exercising substantial executive authority has ever been headed by a single person. Until now."

In 1935, however, the Supreme Court carved out an exception to Myers and Article II by permitting Congress to create independent agencies that exercise executive power. See Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935). An agency is considered “independent” when the agency heads are removable by the President only for cause, not at will, and therefore are not supervised or directed by the President. Examples of independent agencies include well-known bodies such as the Federal Communications Commission, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, the National Labor Relations Board, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission... To help mitigate the risk to individual liberty, the independent agencies, although not checked by the President, have historically been headed by multiple commissioners, directors, or board members who act as checks on one another. Each independent agency has traditionally been established, in the Supreme Court’s words, as a “body of experts appointed by law and informed by experience."

Although the Federal Reserve, unlike the CFPB, has a seven-member Board of Governors, several aspects of their governance are similar: the CFPB Director, like the seven members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, is nominated by the President and approved by the Senate. The CFPB Director's term length is 5 years, compared to 14 years for the Governors-- but importantly, both have terms longer than the 4-year Presidential term. The Chair and Vice Chair of the Fed are nominated from the Governors by the President and approved by the Senate for a 4-year term. Both the CFPB Director and the Fed Chair are required to give semi-annual reports to Congress. See these resources for a more detailed comparison of the structure and governance of independent federal agencies.

I find it striking that the phrase individual liberty appears 32 times in the 110-page decision. The very first paragraph states, "This is a case about executive power and individual liberty. The U.S. Government’s executive power to enforce federal law against private citizens – for example, to bring criminal prosecutions and civil enforcement actions – is essential to societal order and progress, but simultaneously a grave threat to individual liberty."

Even though both the CFPB and the Fed have substantial financial regulatory authority, the discourse on Federal Reserve independence does not focus so heavily on liberty (I've barely come across the word at all in my readings on the subject); instead, it focuses on independence as a potential threat to accountability. As I have previously written, "the term accountability has become 'an ever-expanding concept,'" and one that is often not usefully defined. The same might be said for the term liberty. Still, the two terms have different connotations. Accountability requires that the institution carry out its responsibilities satisfactorily, while liberty is more about what the institution doesn't do.

Accountability is a key concept in the literature on delegation of tasks to technocrats or politicians. In "Bureaucrats or Politicians?," Alberto Alesini and Guido Tabellini (2007) build a model in which politicians are held accountable by their desire for re-election, while top-level bureaucrats are held accountable by "career concerns." The social desirability of delegating a task to an unelected bureaucrat depends on how the task affects the distribution of resources or advantages-- and thus, on the strength of interest-group political pressure. As Alan Blinder writes:

"Some public policy decisions have -- or are perceived to have -- mostly general impacts, affecting most citizens in similar ways. Monetary policy, for example...is usually thought of as affecting the whole economy rather than particular groups or industries. Other public policies are more naturally thought of as particularist, conferring benefits and imposing costs on identifiable groups...When the issues are particularist, the visible hand of interest-group politics is likely to be most pernicious -- which would seem to support delegating authority to unelected experts. But these are precisely the issues that require the heaviest doses of value judgments to decide who should win and lose. Such judgments are inherently and appropriately political. It's a genuine dilemma."The Federal Reserve's Congressional mandate is to promote price stability and maximum employment. Federal Reserve independence is intended to promote these objectives by alleviating political pressure to pursue overly-accomodative monetary policy. Of course, as we have seen in recent years, the interest-group politics of central banking are more nuanced than a simple desire by incumbents for inflation. Interest rate policy and inflation affect different segments of the population in different ways. The CFPB is supposed to enforce federal consumer financial laws and protect consumers in financial markets. The average benefits of the CFPB to individual consumers is probably fairly small, while the costs of regulation and enforcement to a smaller number of financial companies is large. This asymmetry means that political pressure on a financial regulator like the CFPB (or on the Fed, in its regulatory role) is likely to come from the side of the financial institutions. In Blinder's logic, this confers a large value on the delegation of authority to technocrats, while at the same time raising the importance of accountability for political legitimacy.

Tyler Cowen writes, "I say the regulatory state already has too much arbitrary power, and this [District Court ruling] is a (small) move in the right direction." It is not the reduction of the regulatory state's power that will necessarily enhance either accountability or liberty, but the reduction of the arbitrariness of the regulatory power. This can come about through transparency (which the Fed typically cites as key to the maintenance of accountability), making policies and enforcement more predictable and less retroactive and reducing uncertainty. I don't know that the types of governance changes implied by the District Court ruling (if it holds) will substantially affect the CFPB's transparency or make it any less capable of pursuing its goals, as I tend to agree with Senator Elizabeth Warren's interpretation that the ruling will only require “a small technical tweak.”

Tuesday, September 27, 2016

Why are Long-Run Inflation Expectations Falling?

Randal Verbrugge and I have just published a Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary called "Digging into the Downward Trend in Consumer Inflation Expectations." The piece focuses on long-run inflation expectations--expectations for the next 5 to 10 years-- from the Michigan Survey of Consumers. These expectations have been trending downward since the summer of 2014, around the same time as oil and gas prices started to decline. It might seem natural to conclude that falling gas prices are responsible for the decline in long-run inflation expectations. But we suggest that this may not be the whole story.

First of all, gas prices have exhibited two upward surges since 2014, neither of which was associated with a rise in long-run inflation expectations. Second, the correlation between gas prices and inflation expectations (a relationship I explore in much more detail in this working paper) appears too weak to explain the size of the decline. So what else could be going on?

If you look at the histogram in Figure 2, below, you can see the distribution of inflation forecasts that consumers give in three different time periods: an early period, the first half of 2014, and the past year. The shaded gray bars correspond to the early period, the red bars to 2014, and the blue bars to the most recent period. Notice that there is some degree of "response heaping" at multiples of 5%. In another paper, I use this response heaping to help quantify consumers' uncertainty about long-run inflation. The idea is that people who are more uncertain about inflation, or have a less precise estimate of what it should be, tend to report a round number-- this is a well-documented tendency in how people communicate imprecision.

The response heaping has declined over time, corresponding to a fall in my consumer inflation uncertainty index for the longer horizon. As we detail in the Commentary, this fall in uncertainty helps explain the decline in the measured median inflation forecast. This is a remnant of the fact that common round forecasts, 5% and 10%, are higher than common non-round forecasts.

There is also a notable change in the distribution of non-round forecasts over time. The biggest change is that 1% forecasts for long-run inflation are much more common than previously (see how the blue bar is higher than the red and gray bars for 1% inflation). I think this is an important sign that some consumers (probably those that are more informed about the economy and inflation) are noticing that inflation has been quite low for an extended period, and are starting to incorporate low inflation into their long-run expectations. More consumers expect 1% inflation than 2%.

First of all, gas prices have exhibited two upward surges since 2014, neither of which was associated with a rise in long-run inflation expectations. Second, the correlation between gas prices and inflation expectations (a relationship I explore in much more detail in this working paper) appears too weak to explain the size of the decline. So what else could be going on?

If you look at the histogram in Figure 2, below, you can see the distribution of inflation forecasts that consumers give in three different time periods: an early period, the first half of 2014, and the past year. The shaded gray bars correspond to the early period, the red bars to 2014, and the blue bars to the most recent period. Notice that there is some degree of "response heaping" at multiples of 5%. In another paper, I use this response heaping to help quantify consumers' uncertainty about long-run inflation. The idea is that people who are more uncertain about inflation, or have a less precise estimate of what it should be, tend to report a round number-- this is a well-documented tendency in how people communicate imprecision.

The response heaping has declined over time, corresponding to a fall in my consumer inflation uncertainty index for the longer horizon. As we detail in the Commentary, this fall in uncertainty helps explain the decline in the measured median inflation forecast. This is a remnant of the fact that common round forecasts, 5% and 10%, are higher than common non-round forecasts.

There is also a notable change in the distribution of non-round forecasts over time. The biggest change is that 1% forecasts for long-run inflation are much more common than previously (see how the blue bar is higher than the red and gray bars for 1% inflation). I think this is an important sign that some consumers (probably those that are more informed about the economy and inflation) are noticing that inflation has been quite low for an extended period, and are starting to incorporate low inflation into their long-run expectations. More consumers expect 1% inflation than 2%.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

The Fed on Facebook

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors has now joined you, your grandma, and 1.7 billion of your closest friends on Facebook. A press release on August 18 says that the Fed's Facebook page aims at "increasing the accessibility and availability of Federal Reserve Board news and educational content." This news is especially interesting to me, since a chapter of my dissertation-- now my working paper "Fed Speak on Main Street"-- includes some commentary on the Federal Reserve's use of social media.

When I wrote the paper, though the Board of Governors did not have a Facebook page, the Regional Federal Reserve Banks did. I noted that the most popular of these, the San Francisco Fed's page, had around 5000 "likes" (compared to 4.5 million for the White House.) I wrote in my conclusion that "The Fed has begun to use interactive new media such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, but its ad hoc approach to these platforms has resulted in a relatively small reach. Federal Reserve efforts to communicate via these media should continue to be evaluated and refined."

About a year later, the San Francisco Fed is up to around 6000 "likes," while the brand new Board of Governors page already has over 14,000. Only a handful of people post comments on the Regional Fed pages, and they are relatively benign. "Great story! I loved it!" and the SF Fed's response, "So glad you liked it, Ellen!" are the only comments below one recent story. Even critical comments are fairly measured: "adding more money into RE market only inflates housing prices, & creates more deserted neighborhoods," following a story on affordable housing in the Bay Area.

On the Board of Governors' page, however, hundreds of almost exclusively negative and outraged comments follow every piece of content. Several news stories describe the page as overrun by "trolls." "Tell me more about the private meeting on Jekyll island and the plans for public prosperity that some of the worlds richest and most powerful bankers made in secret, please," writes a commenter following a post about who owns the Fed.

It is not too surprising that the Board's page has drawn so much more attention than those of the reserve banks. One of the biggest recurrent debates since before the foundation of the Fed surrounds the degree of centralization of power that is appropriate. The Fed's unusual structure reflects a string of compromises that leaves many unsatisfied. The Board in Washington, to many of the Fed's critics, represents unappealing centralization. To be sure, many of the commenters are likely unaware of the Fed's structure, and maybe of the existence of the regional Federal Reserve Banks. They know only to blame "the Fed," which to them is synonymous with the Board of Governors.

In my paper, I look at data from polls that have asked people a variety of questions about the Fed and the Fed Chair. Polls that ask people about who they credit or blame for economic performance appear in the table below. Most people don't think to blame the Fed for economic problems. If asked explicitly whether the Fed should be blamed, many say yes, but many others are unsure. Commenters on the Facebook page are not a representative sample of the population, of course. They are the ones who do blame the Fed.

Arguably, the negative attention on the Fed Board's page is better than no attention at all. As long as they don't start censoring negative comments-- and maybe even consider responding to some common concerns in press conferences or speeches?-- I think this could actually help their reputation for transparency and accountability. It will also be interesting to see whether the rate of interaction with the page dwindles off after it loses novelty.

When I wrote the paper, though the Board of Governors did not have a Facebook page, the Regional Federal Reserve Banks did. I noted that the most popular of these, the San Francisco Fed's page, had around 5000 "likes" (compared to 4.5 million for the White House.) I wrote in my conclusion that "The Fed has begun to use interactive new media such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, but its ad hoc approach to these platforms has resulted in a relatively small reach. Federal Reserve efforts to communicate via these media should continue to be evaluated and refined."

About a year later, the San Francisco Fed is up to around 6000 "likes," while the brand new Board of Governors page already has over 14,000. Only a handful of people post comments on the Regional Fed pages, and they are relatively benign. "Great story! I loved it!" and the SF Fed's response, "So glad you liked it, Ellen!" are the only comments below one recent story. Even critical comments are fairly measured: "adding more money into RE market only inflates housing prices, & creates more deserted neighborhoods," following a story on affordable housing in the Bay Area.

On the Board of Governors' page, however, hundreds of almost exclusively negative and outraged comments follow every piece of content. Several news stories describe the page as overrun by "trolls." "Tell me more about the private meeting on Jekyll island and the plans for public prosperity that some of the worlds richest and most powerful bankers made in secret, please," writes a commenter following a post about who owns the Fed.

It is not too surprising that the Board's page has drawn so much more attention than those of the reserve banks. One of the biggest recurrent debates since before the foundation of the Fed surrounds the degree of centralization of power that is appropriate. The Fed's unusual structure reflects a string of compromises that leaves many unsatisfied. The Board in Washington, to many of the Fed's critics, represents unappealing centralization. To be sure, many of the commenters are likely unaware of the Fed's structure, and maybe of the existence of the regional Federal Reserve Banks. They know only to blame "the Fed," which to them is synonymous with the Board of Governors.

In my paper, I look at data from polls that have asked people a variety of questions about the Fed and the Fed Chair. Polls that ask people about who they credit or blame for economic performance appear in the table below. Most people don't think to blame the Fed for economic problems. If asked explicitly whether the Fed should be blamed, many say yes, but many others are unsure. Commenters on the Facebook page are not a representative sample of the population, of course. They are the ones who do blame the Fed.

Arguably, the negative attention on the Fed Board's page is better than no attention at all. As long as they don't start censoring negative comments-- and maybe even consider responding to some common concerns in press conferences or speeches?-- I think this could actually help their reputation for transparency and accountability. It will also be interesting to see whether the rate of interaction with the page dwindles off after it loses novelty.

Thursday, July 21, 2016

Inflation Uncertainty Update and Rise in Below-Target Inflation Expectations

In my working paper "Measuring Uncertainty Based on Rounding: New Method and Application to Inflation Expectations," I develop a new measure of consumers' uncertainty about future inflation. The measure is based on a well-documented tendency of people to use round numbers to convey uncertainty or imprecision across a wide variety of contexts. As I detail in the paper, a strikingly large share of respondents on the Michigan Survey of Consumers report inflation expectations that are a multiple of 5%. I exploits variation over time in the distribution of survey responses (in particular, the amount of "response heaping" around multiples of 5) to create inflation uncertainty indices for the one-year and five-to-ten-year horizons.

As new Michigan Survey data becomes available, I have been updating the indices and posting them here. I previously blogged about the update through November 2015. Now that a few more months of data are publicly available, I have updated the indices through June 2016. Figure 1, below, shows the updated indices. Figure 2 zooms in on more recent years and smooths with a moving average filter. You can see that short-horizon uncertainty has been falling since its historical high point in the Great Recession, and long-horizon uncertainty has been at an historical low.

The change in response patterns from 2015 to 2016 is quite interesting. Figure 3 shows histograms of the short-horizon inflation expectation responses given in 2015 and in the first half of 2016. The brown bars show the share of respondents in 2015 who gave each response, and the black lines show the share in 2016. For both years, heaping at multiples of 5 is apparent when you observe the spikes at 5 (but not 4 or 6) and at 10 (but not 9 or 11). However, it is less sharp than in other years when the uncertainty index was higher. But also notice that in 2016, the share of 0% and 1% responses rose and the share of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10% responses fell relative to 2015.

Some respondents take the survey twice with a 6-month gap, so we can see how people switch their responses. Of the respondents who chose a 2% forecast in the second half of 2015 (those who were possible aware of the 2% target), 18% switched to a 0% forecast and 24% switched to a 1% forecast when they took the survey again in 2016. The rise in 1% responses seems most noteworthy to me-- are people finally starting to notice slightly-below-target inflation and incorporate it into their expectations? I think it's too early to say, but worth tracking.

As new Michigan Survey data becomes available, I have been updating the indices and posting them here. I previously blogged about the update through November 2015. Now that a few more months of data are publicly available, I have updated the indices through June 2016. Figure 1, below, shows the updated indices. Figure 2 zooms in on more recent years and smooths with a moving average filter. You can see that short-horizon uncertainty has been falling since its historical high point in the Great Recession, and long-horizon uncertainty has been at an historical low.

|

| Figure 1: Consumer inflation uncertainty index developed in Binder (2015) using data from the University of Michigan Survey of Consumers. To download updated data, visit https://sites.google.com/site/inflationuncertainty/. |

|

| Figure 2: Consumer inflation uncertainty index (centered 3-month moving average) developed in Binder (2015) using data from the University of Michigan Survey of Consumers. To download updated data, visit https://sites.google.com/site/inflationuncertainty/. |

The change in response patterns from 2015 to 2016 is quite interesting. Figure 3 shows histograms of the short-horizon inflation expectation responses given in 2015 and in the first half of 2016. The brown bars show the share of respondents in 2015 who gave each response, and the black lines show the share in 2016. For both years, heaping at multiples of 5 is apparent when you observe the spikes at 5 (but not 4 or 6) and at 10 (but not 9 or 11). However, it is less sharp than in other years when the uncertainty index was higher. But also notice that in 2016, the share of 0% and 1% responses rose and the share of 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10% responses fell relative to 2015.

Some respondents take the survey twice with a 6-month gap, so we can see how people switch their responses. Of the respondents who chose a 2% forecast in the second half of 2015 (those who were possible aware of the 2% target), 18% switched to a 0% forecast and 24% switched to a 1% forecast when they took the survey again in 2016. The rise in 1% responses seems most noteworthy to me-- are people finally starting to notice slightly-below-target inflation and incorporate it into their expectations? I think it's too early to say, but worth tracking.

|

| Figure 3: Created by Binder with data from University of Michigan Survey of Consumers |

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Behavioral Economics Then and Now

“Although it has never been clear whether the consumer needs to be protected from his own folly or from the rapaciousness of those who feed on him, consumer protection is a topic of intense current interest in the courts, in the legislatures, and in the law schools." So write James J. White and Frank W. Munger Jr. in a 1971 article from the Michigan Law Review.

Today, it is not uncommon for behavioral economists to weigh in on financial regulatory policy and consumer protection. White and Munger, not economists but lawyers, played the role of behavioral economists before the phrase was even coined. They managed to anticipate many of the hypotheses and themes that would later dominate behavioral economics-- but with more informal and colorful language. A number of new legislative and judicial acts in the late 1960s provided the impetus for their study:

"Congress has passed the Truth-in-Lending Act; the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws has proposed the Uniform Consumer Credit Code; and many states have enacted retail installment sales acts to update and supplement their long-standing usury laws. These legislative and judicial acts have always relied, at best, on anecdotal knowledge of consumer behavior. In this Article we offer the results of an empirical study of a small slice of consumer behavior in the use of installment credit.

In their recent efforts, the legislatures, by imposing new interest rate disclosure requirements on installment lenders, have sought to protect the consumer against pressures to borrow money at a higher rate of interest than he can afford or need pay. The hope, if not the expectation, of the drafters of such disclosure legislation is that the consumer who is made aware of interest rates will seek the lowest-priced lender or will decide not to borrow. This migration of the consumers to the lowest-priced lender will, so the argument goes, require the higher-priced lender to reduce his rate in order to retain his business. These hopes and expectations are founded on the proposition that the consumer is largely ignorant of the interest rate that he pays; this ignorance presumably keeps him from going to a lender with cheaper rates. Knowledge of interest rates, it is believed, will rectify this defect…”

Here comes their "squatting baboon" metaphor:

“Presumably, consumers in a perfect market will behave like water in a pond, which gravitates to the lowest point-i.e., consumer borrowers should all tum to the lender that gives the cheapest loan. We began this project with a strong suspicion-based on the observations of others-that the consumer credit market is far from perfect and that water governed by the force of gravity is a poor metaphor with which to describe the behavior of consumer debtors. The consumer debtor's choice of creditor clearly involves consideration of many factors besides interest rate. Therefore, a metaphor that better describes our suspicions about the borrower's behavior in a market in which rate differences appear involves a group of monkeys in a cage with a new baboon of unknown temperament. The baboon squats in one comer of the cage near some choice, ripe bananas. In the far comer of the cage is a supply of wilted greens and spoiled bananas, the monkeys' usual fare. Some of the monkeys continue eating their usual fare because they are unaware of the new bananas and the visitor. Other monkeys observe the new bananas but do not approach them. Still others, more daring or intelligent than the rest, seek ways of snatching an occasional banana from the baboon's stock. The baboon strikes at all the brown monkeys but he permits black monkeys to eat without interference. Yet many of the black monkeys make no attempt to eat. One suspects that a social scientist who interviewed the members of the monkey tribe about their experience would find that many of those who saw and appreciated the choice bananas would be unable to articulate the reasons for their failure to eat any of them. The social scientist might also discover that a few who looked at the baboon in obvious fright would nevertheless deny that they were afraid. In addition, he might find that some were so busy picking fleas or nursing that they did not observe the choice bananas at all. We suspected that consumer borrowers had similarly diverse reasons for their behavior.

We presumed that some paid high interest rates only because of ignorance of lower rates and that others correctly concluded that they could not qualify for a cheaper loan than they received. Others, we suspected, were merely too lazy or too fearful of bankers to seek lower rates.”

A majority of the sample did not know the rate at which they had borrowed. Most had allowed the auto dealer to arrange the loan rather than shopping for the lowest rate. Even if they knew that lower rates were available elsewhere, they declined to shop around. The authors find differences in financial sophistication, education, and job characteristics between consumers who shopped around for lower rates and those who did not. They conclude:

“The results of our study suggest that, at least with regard to auto loans, the disclosure provisions of the Truth-in-Lending Act will be largely ineffective in changing consumer behavior patterns. Certainly the Act will not improve the status of those who already know that lower rates are available elsewhere. And we discovered no evidence that knowledge of the interest rate-which, even under the Act will usually come after a tentative agreement to purchase a specified car has been reached-will stimulate a substantial percentage of consumers to shop for a lower rate elsewhere.”The authors come down as pessimistic about the Truth-in-Lending Act, but make no new policy recommendations of their own. If they were writing today, instead of just predicting that a policy would be ineffective, they might suggest ways to design the policy to "nudge" consumers to make different decisions. The Truth-in-Lending Act has been amended numerous times over the years, and was placed under the authority of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) by the Dodd-Frank Act. Behavioral economics has played a central role in the work of the CFPB. But the active application of behavioral law and economics to regulatory policy is not universally accepted. For example, Todd Zwicki writes:

"We argue that even if the findings of behavioral economics are sound and robust, and the recommendations of behavioral law and economics are coherent (two heroic assumptions, especially the latter), there still remain vexing problems of actually implementing behavioral economics in a real-world political context. In particular, the realities of the political and regulatory process suggests that the trip from the laboratory to the real-world crafting of regulations that will improve consumers’ lives is a long and rocky one."Zwicki expands this argument in a paper coauthored with Adam Christopher Smith. While I'm not convinced that their rather negative portrayal of the CFPB is warranted, I do think the paper presents some provocative cautions about how behavioral economics is applied to policy--especially the warning against "selective modeling of behavioral bias," which I have heard even top behavioral economists caution against.

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

Downside Inflation Risk

Earlier this month, New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley gave a speech on "The U.S. Economic Outlook and Implications for Monetary Policy." Like other Fed officials, Dudley expressed concern about falling inflation expectations:

The 22 basis-points decline in 3-year inflation expectations that Dudley referred to is the median for all consumers. If you look at the table below, the decline is more than twice as large for consumers with income above $50,000 per year.

This might be important since high-income consumers' expectations appear to be a stronger driver of actual inflation dynamics than the median consumer's expectations, probably because they are a better proxy for price-setters' expectations. These higher-income consumers' inflation expectations were at or above 3% from the start of the survey in 2013 through mid-2014, and are now at their lowest recorded level. Lower-income consumers' expectations have risen slightly from a low of 2.72% in September 2015. We need a few more months of data to separate trend from noise, but if anything this should strengthen Dudley's concern about downside risks to inflation.

With respect to the risks to the inflation outlook, the most concerning is the possibility that inflation expectations become unanchored to the downside. This would be problematic were it to occur because inflation expectations are an important driver of actual inflation. If inflation expectations become unanchored to the downside, it would become much more difficult to push inflation back up to the central bank’s objective.Dudley, perhaps because of his New York Fed affiliation, pointed to the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations as his preferred indicator of inflation expectations. He noted that on this survey, "The median of 3-year inflation expectations has declined over the past year, falling by 22 basis points to 2.8 percent. While the magnitude of this decline is small, I think it is noteworthy because the current reading is below where we have been during the survey history."

The 22 basis-points decline in 3-year inflation expectations that Dudley referred to is the median for all consumers. If you look at the table below, the decline is more than twice as large for consumers with income above $50,000 per year.

|

| Source: Data from Survey of Consumer Expectations, © 2013-2015 Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY). Calculations by Carola Binder. |

Sunday, January 10, 2016

Household Inflation Uncertainty Update

In my job market paper last year, I constructed a new measure of households' inflation uncertainty based on people's tendency to use round numbers when they report their inflation expectations on the Michigan Survey of Consumers. The monthly consumer inflation uncertainty index is available at a short horizon (one-year-ahead) and a long horizon (five-to-ten-years ahead). I explain the construction of the indices in more detail, and update them periodically, at the Inflation Uncertainty website, where you can also download the indices.