1. Rajan Signals India Inflation Target Amid Vote Tension (Bloomberg): India central bank Governor Raghuram Rajan may attempt to make inflation the bank's primary priority. Rajan says, "If the government policies in aggregate prove to be

expansionary, we will have to adjust policies ourselves to meet

the overall disinflationary process. We can’t throw up our hands in some

sense and say there is nothing we can do because of the fiscal

dominance."

2. Hungary Rate-Cut Resolve Challenged by Investors as Forint Drops (Bloomberg): Inflation in Hungary is at its lowest since 1970. Central banks in Turkey and South Africa are raising rates to try and stop falling currencies, but the Hungarian central bank faces a challenge because monetary easing is more appropriate to its inflation and growth conditions.

3. Inflation in Euro Zone Falls, and a 12% Jobless Rate Doesn’t Budge (NYT): The 0.7 percent inflation rate may have surprised the ECB.

4. Japan’s Inflation Accelerates as Abe Seeks Wage Gains (Bloomberg): Japan's inflation has inched up, but the real test will come at the annual wage talks in April. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has met five times since September with business and

union leaders to encourage them to raise salaries, which have risen slower than prices.

Showing posts with label Japan. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Japan. Show all posts

Friday, January 31, 2014

Monday, October 28, 2013

Abenomics and Japanese Inflation Expectations

Paul Krugman has an "extremely wonky" new post about how to measure inflation expectations in Japan under Abenomics. The measure uses Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS), the topic of a series I am writing on this blog and the Noahpinion blog. Inflation-protected securities may be used to infer breakeven inflation expectations from the market. Japan's market in inflation-protected securities is considered too thin to provide useful information about expectations, so Krugman, building on the approach of Benjamin Mandel and Geoffrey Barnes, combines US TIPS data and real exchange rate data to measure Japanese inflation expectations:

I took the implied 10-year breakeven inflation rate from US TIPS, minus the 10-year interest rate differential, plus the real appreciation Japan would experience if the real exchange rate against the dollar 10 years from now were to return to its level in January 2010. You can adjust this as you like with whatever your estimate of the difference between the 1-2010 rate and the equilibrium rate is; it will just shift the line up or down.The result is inflation expectations just below 0 until the start of 2012. Expectations rise to almost 3% by May 2013, then fall to around 1.5% by July 2013. Krugman writes:

I have my doubts about the apparent decline in recent months. It’s being driven not by events in Japan but by the taper scare, which drove up US rates. There is a question about why that rise in US rates didn’t produce a lot more yen depreciation, but something seems off here.

The main point, however, is that this measure does suggest a substantial rise in expected inflation since Abenomics began, which is good news.Another indicator of inflation expectations is the Bank of Japan's Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior. According to this survey, there is no evidence of a decline in inflation expectations in recent months. The most recent survey, from June 2013, shows a continued rise in one-year-ahead expectations from December to March to June. The June average expectation was 5.1% and the median expectation was 3%. In 2010, the median expectation was 0% and the mean around 2%. Longer-term inflation expectations (which should correspond more closely to Krugman's measure) are also rising, though more gradually.

|

| Source: Bank of Japan Opinion Survey |

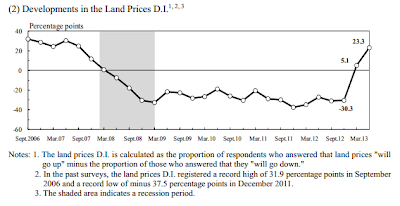

Also at a new high is the survey's measure of land price expectations. This is a newer development; the sharp rise began in late 2012:

Even if the expectations reported by surveyed households are not an accurate indicator of what will actually happen with inflation, they are still relevant. In the United States, households in the Michigan Survey of Consumers report higher inflation expectations than professional forecasts or TIPS-based measures. A new paper by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Olivier Coibion, summarized by Jim Hamilton, suggests that the household expectations are important in explaining the "missing deflation" of the past few years.

Neither Krugman's US TIPS-based measure nor the household survey-based measure are perfect indicators of Japanese inflation expectations. But the fact that both indicate a rise in expectations since Abenomics began, combined with the dramatic increase in the index of land price expectations, convinces me at least qualitatively that expectations are rising, though I'd put huge error bars on any quantitative estimate.

Krugman calls the rise in inflation expectations "good news." I agree, with a qualification. In an earlier post, "What Does Abenomics Feel Like?", I noted that Japanese consumers viewed rising prices extremely unfavorably. This, unsurprisingly, has not changed. There are, after all, no significant changes in perceptions of employment and working conditions. In the mind of a typical consumer, more concerned with her own purchasing power than with liquidity trap economics, rising prices are not such a signifier of salvation.

But there is a glimmer of hope. Consumers' perceptions of current economic conditions and of the economy's growth potential are both looking-- well, not bright, but brighter than before.

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

Japanese Wage Data Not All That Spectacular (Exception: Finance Industry)

The results of Japan's Provisional Report of Monthly Labour Survey for July 2013 are now available. The Wall Street Journal calls the wage data "not all that gloomy," citing the fact that nominal earnings are up 0.4%. According to the article,

Both the contractual and special cash earning changes vary a lot across industries. In the finance and insurance industry, total cash earnings were up 1.5% and special cash earnings were up 17.8%. On the other extreme is the education and learning support industry, for which total cash earnings were down 6.1% and special cash earnings were down 20.1%.

The total real wage is down 0.4% from the same month a year ago. On a seasonally-adjusted basis, the number of regular employees has neither increased nor decreased. If any readers are adept at interpreting this survey data, please chime in with any insights I have missed.

I believe my earlier post--"What Does Abenomics Feel Like?"-- is still quite relevant.

"That’s good news for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as he has made wage growth a key measure of success for Abenomics, which seeks to lift Japan out of 15 years of deflation. While the aggressive monetary easing and government spending measures have pushed up production as well as prices, Mr. Abe has acknowledged that without substantial wage growth, there can be no sustainable economic expansion."I think it's too early to claim good news or to call this substantial wage growth. Here are just a few quick points from my skim-through of the survey results. The 0.4% increase that the article refers to is for nominal total cash earnings (compared to the same month a year ago), for all industries. This can be broken down into a 0.3% fall in contractual cash earnings and a 2.1% increase in special cash earnings. Companies are giving summer bonuses but not committing to presumably more permanent base-pay increases.

Both the contractual and special cash earning changes vary a lot across industries. In the finance and insurance industry, total cash earnings were up 1.5% and special cash earnings were up 17.8%. On the other extreme is the education and learning support industry, for which total cash earnings were down 6.1% and special cash earnings were down 20.1%.

The total real wage is down 0.4% from the same month a year ago. On a seasonally-adjusted basis, the number of regular employees has neither increased nor decreased. If any readers are adept at interpreting this survey data, please chime in with any insights I have missed.

I believe my earlier post--"What Does Abenomics Feel Like?"-- is still quite relevant.

Monday, August 19, 2013

What Does Abenomics Feel Like?

Depending on whom you ask and when, Abenomics is or is not working, and Japan is or is not entering a recovery. What if you ask the people of Japan?

The closest thing to asking them is looking at the Bank of Japan's Opinion Survey on the General Public's Views and Behavior, a quarterly survey with a nationwide sample of 4,000 individuals who are at least 20 years old. The results from the June 2013 survey were recently released, giving us a glimpse of how the general public of Japan is experiencing economic life under Abe.

When asked, in the abstract, about the "growth potential" of the Japanese economy, responses are less pessimistic than in previous quarters. But when asked about their own household's experience, the situation still looks pretty bleak. In one question, respondents are asked, "What do you think of your household circumstances compared with one year ago?" Only 4.9% say they are better off, while 39.2% say they are worse off, and the rest say it is difficult to tell. While not great, these numbers are a minor improvement over a year prior, when only 3.6% said they were better off and 47% said they were worse off. Of the households who reported worse circumstances, 73% said a reason was that their income decreased and 42% said a reason was that their income was not likely to increase in the future (they could choose multiple options).

The 4.9% of households who thought their circumstances improved were also asked why. About 22% responded that their interest income and dividend payments increased and 26% said it was because the value of their assets increased. Insofar as Abenomics has led to a rising Nikkei, this has only been enough to lead about one or two percent of households to notice improvements in their circumstances. (More households might have benefited from the rise, but not enough to offset other challenges.) The stock market rise greatly increased the net profits of regional banks, but the benefits don't seem to have been widely spread.

Positive inflation and higher inflation expectations are cornerstone goals of Abenomics. Deflation has plagued the Japanese economy since the latter half of the 1990s. Japan's CPI less food and energy rose 0.2% from a year earlier in June, the largest rise since 2008. At Bloomberg, Toru Fujioka and Andy Sharp report that "the world’s third-biggest economy may be starting to shake off 15 years of deflation." Fujioka and Sharp declare this a "Boost for Abe," and write that "the increase in consumer prices could stoke inflation expectations and encourage companies and consumers to spend more, bolstering the economic recovery."

The June 2013 survey shows that consumers are noticing rising prices and expect prices to continue to rise. In particular, 50.5% of survey respondents felt that prices had gone up in the previous year, and over 80% expect prices to go up over the next year. However, of the respondents who noticed rising prices, 81.6% described the price rise as "rather unfavorable." This makes it seem unlikely that stoked inflation expectations will encourage consumers to spend more. In fact, 44.8% of respondents plan to decrease their spending over the next year, and only 6.1% plan to increase spending.

I previously wrote a post about how Europeans really dislike inflation, even when it is low, but I think the reason Japanese consumers dread rising prices is different. If price inflation is not accompanied by wage inflation--and is not expected to be-- then the pass-through from inflation expectations to consumer spending is broken. Fujioka and Sharp quote Akiyoshi Takumori, chief economist at Sumitomo Mitsui Asset Management, saying “business executives must have forgotten how to increase pay after decades of deflation." Japanese companies are reluctant to raise base pay. In June, while average total monthly cash earnings, including overtime and bonuses, rose 0.1%, regular pay fell 0.2%. The rise in total earnings was attributable to higher summer bonuses. Over 80% of survey respondents are slightly or quite worried about working conditions such as pay, job position, and benefits.

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

Japan and the Formation of Inflation Expectations

With the Bank of Japan's adoption of a 2% inflation target making headline news, it seems like a good time to discuss some recent research on the psychology of inflation expecations by Berkeley Professor Ulrike Malmendier, who was recently awarded the 2013 Fischer Black Prize from the American Finance Association. This biennial prize honors the top finance scholar under the age of 40 years old. Malmendier works in the intersection between finance and behavioral economics and is known for her incredible creativity.

Blanchflower and Mac Coille also summarize three paths through which inflation expectations matter:

Here is the abstract of Malmendier's paper with Steven Nagel titled "Learning from Inflation Experiences":

How do individuals form expectations about future inflation? We propose that past inflation experiences are an important determinant absent from existing models. Individuals overweigh inflation rates experienced during their life-times so far, relative to other historical data on inflation. Differently from adaptive-learning models, experience-based learning implies that young individuals place more weight on recently experienced inflation than older individuals since recent experiences make up a larger part of their life-times so far. Averaged across cohorts, expectations resemble those obtained from constant-gain learning algorithms common in macroeconomics, but the speed of learning differs between cohorts.

Using 54 years of microdata on inflation expectations from the Reuters/Michigan Survey of Consumers, we show that differences in life-time experiences strongly predict differences in subjective inflation expectations. As implied by the model, young individuals place more weight on recently experienced inflation than older individuals. We find substantial disagreement between young and old individuals about future inflation rates in periods of high surprise inflation, such as the 1970s. The experience effect also helps to predict the time-series of forecast errors in the Reuters/Michigan survey and the Survey of Professional Forecasters, as well as the excess returns on nominal long-term bonds.

Malmendier and Nagel's paper over a time period covering several monetary policy regimes, which differ markedly from that of Japan. But a related paper by David Blanchflower and Conall Mac Coille focuses on the UK, which practices inflation targeting. "The Formation of Inflation Expectations: an Empirical Analysis for the UK" (2009) includes a summary of why inflation expectations matter for monetary policy, and how this is relevant to inflation targeting:

In the neo-Keynesian model (see, for example, Clarida et al. 2000), sticky prices result in forward looking behaviour; inflation today is a function of expected future inflation as well as the pressure of demand, captured in an output gap term. Thus, expectations are deemed to be an important link in the monetary transmission mechanism. Monetary policy can be more successful when long-term inflation expectations are well anchored. Hence, many studies have focused on the question of how to assess the response of inflation expectations to macroeconomic shocks, and whether this is likely to be lower in inflation targeting regimes.

Wages are set on an infrequent basis, thus wage setters have to form a view on future inflation. If inflation is expected to be persistently higher in the future, employees may seek higher nominal wages in order to maintain their purchasing power. This in turn could lead to upward pressure on companies’ output prices, and hence higher consumer prices. Additionally, if companies expect general inflation to be higher in the future, they may be more inclined to raise prices, believing that they can do so without suffering a drop in demand for their output. A third path by which inflation expectations could potentially impact inflation is through their influence on consumption and investment decisions. For a given path of nominal market interest rates, if households and companies expect higher inflation, this implies lower expected real interest rates, making spending more attractive relative to saving.

In Japan, the third path may be most important. The higher inflation target is intended to lower real interest rates and boost consumption and investment. But there is a fourth reason, not listed by Blanchflower and Mac Coille, of particular relevance to Japan. Foreigners' expectations of future inflation affect the value of the currency. the Japanese Ministry of Finance recently revealed a 222.4 billion yen ($2.5 billion) current account deficit-- a measure of how much imports exceed exports. When people expect Japanese inflation to be higher in the future, the yen gets less valuable now, because it won't be able to buy as much stuff later; the yen weakens. But in this case, weakness is not necessarily bad. A weaker yen means that Japanese people will find it more expensive to import stuff, so they will import less. Likewise, people outside of Japan will find it cheaper to buy Japanese stuff, so Japan will export more. This helps shrink the current account deficit. And depending on the sizes of the income and substitution effects, Japanese consumers may buy more Japanese products.

Under inflation targeting in the UK, even though inflation expectations are reasonably well anchored, and median expectations are around the inflation target, there is substantial heterogeneity across agents in their inflation expectations. Malmendier and Nagel's paper provides a behavioral theory to explain part of this heterogeneity based on agents' heterogeneous past experiences of inflation. Heterogeneous inflation expectations have the potential to affect the workings of all the paths through which inflation expectations matter. We need to understand not only how Japan's inflation target will influence median inflation expectations, but also how it will affect expectations of price setters, wage setters, borrowers, savers, exporters, trade partners, etc. More than likely, these groups differ significantly in their demographics, have had different experiences, and thus form different expectations of inflation. (For reference, the graph below displays Japanese inflation, interest rates, real GDP per capita growth rate, and M2 growth rate. Japan has not seen 2% inflation since 1997.) Extensions of Malmendier's research to other countries and monetary regimes will be very useful in understanding the effects of monetary policy.

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Inflation Targeting Pressure in Japan

I recently wrote an article for the forthcoming Global Economic History Encyclopedia about inflation targeting. I only submitted the article for editing a few days ago, but it looks like it may be due for updates before the encyclopedia even comes out! The reason is news that Shinzo Abe, future premier of Japan, is pressuring the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to adopt a 2% inflation target. Apparently, if the bank refuses, Abe will try to change the law guaranteeing BOJ independence. Currently, the BOJ has a 1% inflation target. This is pretty big news, but I haven't seen any economist's analysis in the press yet, so I'll try to walk through some of the basic implications.

The Japanese economy experienced deflation and economic stagnation in the 1990s, recovered somewhat from 2003 to 2007, then fell back into recession. Consumer prices have fallen 6.8% since 1997. Richard Koo's book calls the extended Japanese recession "The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics" because of the light it can shed on macroeconomic theory. Paul Krugman has also repeatedly looked to Japan to study the macroeconomy under conditions of recession, deflation, and the liquidity trap.

To analyze the news about the possible 2% target, something to keep in mind is the relationship between interest rates and inflation. The nominal interest rate is the real interest rate plus expected inflation. There is a zero lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates, since potential lenders would rather just hold cash than lend at negative nominal interest rates. Real interest rates affect decisions about spending and investing now versus later, so they affect aggregate demand. Typically in a recession, monetary authorities want to lower interest rates to boost aggregate demand. A certain level of real interest rates would theoretically restore full employment. But, especially when inflation is low or negative, the ZLB on nominal interest rates can prevent the real interest rate from going sufficiently low. This situation is called a liquidity trap, and renders conventional monetary policy obsolete.

Since the real interest rate is the nominal rate minus expected inflation, raising expected inflation can help lower the real interest rate. But raising expectations about future inflation is not a straightforward task. If a central bank starts printing a lot of money, the public still might not believe that it would continue to do so in the future, when the bank's incentives would be different. One purported solution is for the bank to publicly and explicitly commit to an inflation target. The public commitment is intended to add credibility, so that expectations will actually change.

The other relevant relationship is between exchange rates and inflation. If inflation in Japan is expected to be higher, then the yen will have less purchasing power in the future, so the yen will depreciate. Depreciation of the yen makes Japanese exports relatively cheaper and imports relatively more expensive. So a higher inflation target could reduce Japan's trade deficit, which has been large this year.

My final comment is that central bank independence is not a goal in and of itself. It may be a means of arriving at the goal of effective monetary policy, or it may not. Typically, central bank independence does facilitate effective monetary policy by adding credibility. But at the moment, the BOJ is not credible enough to achieve its 1% inflation target. Maybe if the 2% target were instituted by another part of the government considered more credible, it would actually be more effective. In conclusion, I am somewhat hopeful that Japan is headed in a good direction. Either the BOJ will adopt a 2% target, which will be seen as more credible due to government support, or the government will itself impose the target, which would be drastic enough to cause the markets to notice, bringing about some aggregate demand stimulus.

_______________________________________________________

P.S. I haven't written in awhile for two exciting reasons. First, I have been working on articles for the Global Economic History Encyclopedia. Along with inflation targeting, I have written about the euro area, the Basel Accords, the National Monetary Commission, the gold standard, the Glass-Steagall Act, Wildcat Banking, the Credit Anstalt Crisis, and a few others.

Second, I haven't been writing because I was too busy getting married and going on a honeymoon! I married Joe Binder on December 1 at Christ the King Catholic Church in Dallas, TX. Then we drove across the Southwest for our honeymoon, stopping at a lot of national parks and monuments including Carlsbad Caverns, Guadalupe Mountain, White Sands, Tucson, Sedona, the Gila Cliff Dwellings, and the Grand Canyon. We feel so happy and blessed and are excited about our first Christmas together!

The Japanese economy experienced deflation and economic stagnation in the 1990s, recovered somewhat from 2003 to 2007, then fell back into recession. Consumer prices have fallen 6.8% since 1997. Richard Koo's book calls the extended Japanese recession "The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics" because of the light it can shed on macroeconomic theory. Paul Krugman has also repeatedly looked to Japan to study the macroeconomy under conditions of recession, deflation, and the liquidity trap.

To analyze the news about the possible 2% target, something to keep in mind is the relationship between interest rates and inflation. The nominal interest rate is the real interest rate plus expected inflation. There is a zero lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates, since potential lenders would rather just hold cash than lend at negative nominal interest rates. Real interest rates affect decisions about spending and investing now versus later, so they affect aggregate demand. Typically in a recession, monetary authorities want to lower interest rates to boost aggregate demand. A certain level of real interest rates would theoretically restore full employment. But, especially when inflation is low or negative, the ZLB on nominal interest rates can prevent the real interest rate from going sufficiently low. This situation is called a liquidity trap, and renders conventional monetary policy obsolete.

Since the real interest rate is the nominal rate minus expected inflation, raising expected inflation can help lower the real interest rate. But raising expectations about future inflation is not a straightforward task. If a central bank starts printing a lot of money, the public still might not believe that it would continue to do so in the future, when the bank's incentives would be different. One purported solution is for the bank to publicly and explicitly commit to an inflation target. The public commitment is intended to add credibility, so that expectations will actually change.

The other relevant relationship is between exchange rates and inflation. If inflation in Japan is expected to be higher, then the yen will have less purchasing power in the future, so the yen will depreciate. Depreciation of the yen makes Japanese exports relatively cheaper and imports relatively more expensive. So a higher inflation target could reduce Japan's trade deficit, which has been large this year.

My final comment is that central bank independence is not a goal in and of itself. It may be a means of arriving at the goal of effective monetary policy, or it may not. Typically, central bank independence does facilitate effective monetary policy by adding credibility. But at the moment, the BOJ is not credible enough to achieve its 1% inflation target. Maybe if the 2% target were instituted by another part of the government considered more credible, it would actually be more effective. In conclusion, I am somewhat hopeful that Japan is headed in a good direction. Either the BOJ will adopt a 2% target, which will be seen as more credible due to government support, or the government will itself impose the target, which would be drastic enough to cause the markets to notice, bringing about some aggregate demand stimulus.

_______________________________________________________

P.S. I haven't written in awhile for two exciting reasons. First, I have been working on articles for the Global Economic History Encyclopedia. Along with inflation targeting, I have written about the euro area, the Basel Accords, the National Monetary Commission, the gold standard, the Glass-Steagall Act, Wildcat Banking, the Credit Anstalt Crisis, and a few others.

Second, I haven't been writing because I was too busy getting married and going on a honeymoon! I married Joe Binder on December 1 at Christ the King Catholic Church in Dallas, TX. Then we drove across the Southwest for our honeymoon, stopping at a lot of national parks and monuments including Carlsbad Caverns, Guadalupe Mountain, White Sands, Tucson, Sedona, the Gila Cliff Dwellings, and the Grand Canyon. We feel so happy and blessed and are excited about our first Christmas together!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)